The following post is another summary of the work done by Dave Elmore of Wolverhampton University, who is a colleague of mine on the University of Bath Foundation degree. This piece of research was done as part of the Bath course and Dave has kindly allowed me to share it here. For those not aware of the course at Bath, it is a fantastic learning opportunity for any person dedicated to Judo. It covers everything from the Origins and HIstory of Judo to the latest scientific research and modern Judo waza, not to forget Kata also. Applications for the 2010 intake are open now, so please do visit the website and consider signing up.

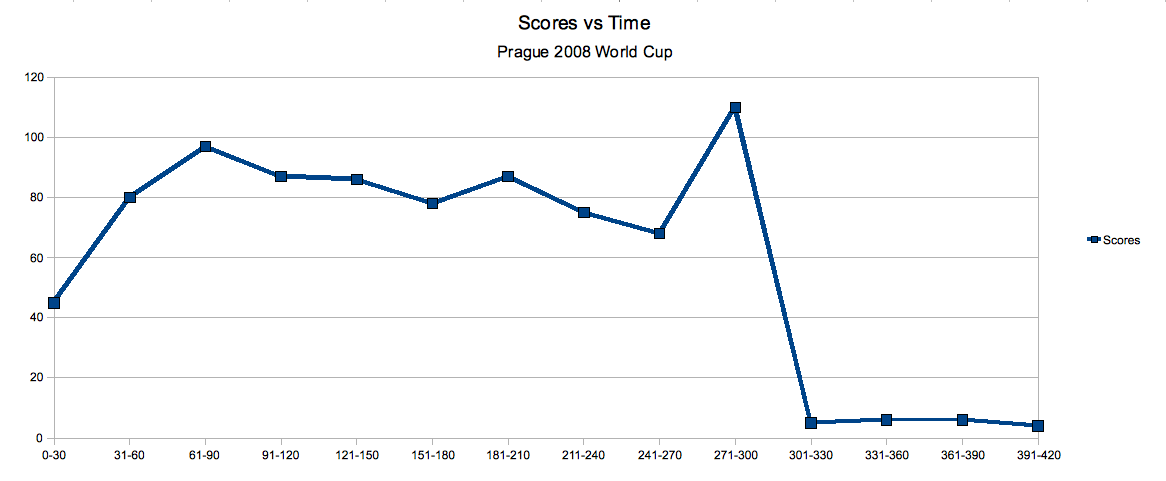

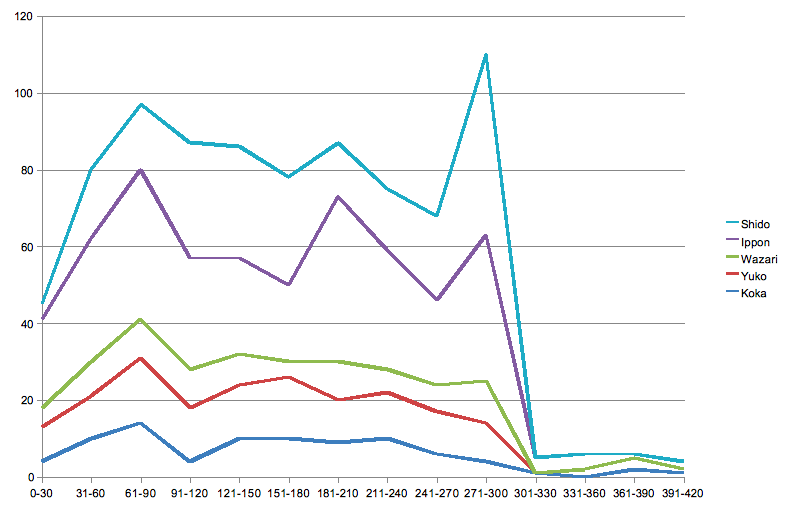

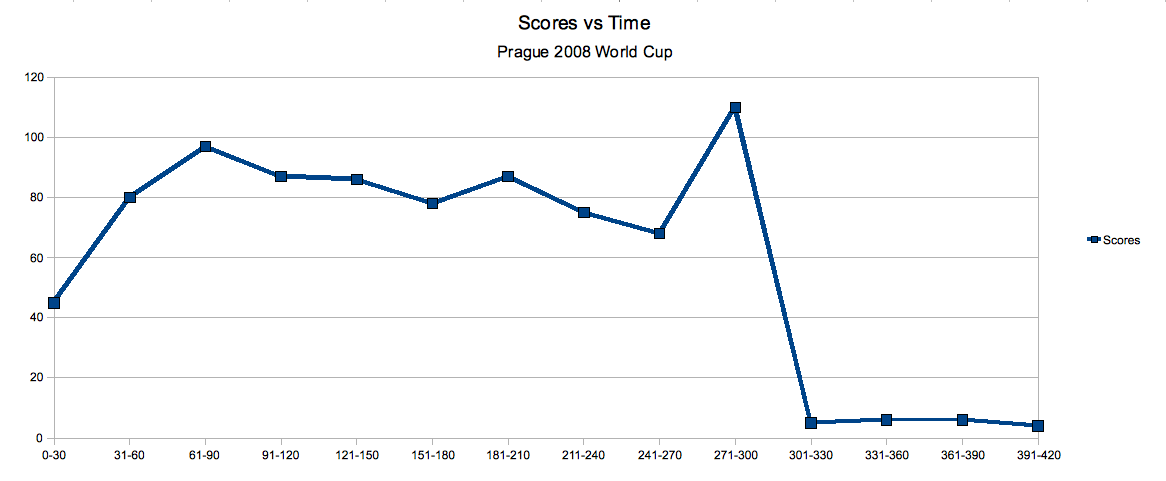

What the chart above shows us very simply is when scores were achieved in matches at this event, broken into 30 second segments. This chart is based on the toal number of score across categories. You can see that during the 21-90 second mark the number of scores is reaches a peak, then drops off; followed by another peak at 271-330 seconds.

This data can be interpretted in a number of ways as players, coaches, physiologists and analysts. Tactically, we can look at this and suggest that our training programmes need to prepare our Judo athletes to expect higher work rates at these two peaks. Strength and Conditioning be it in the gym or in the Dojo could be modelled around the structure shown in the chart.

Of course there is more to the story than this, we need to look deeper before making radical changes to our training regimes.

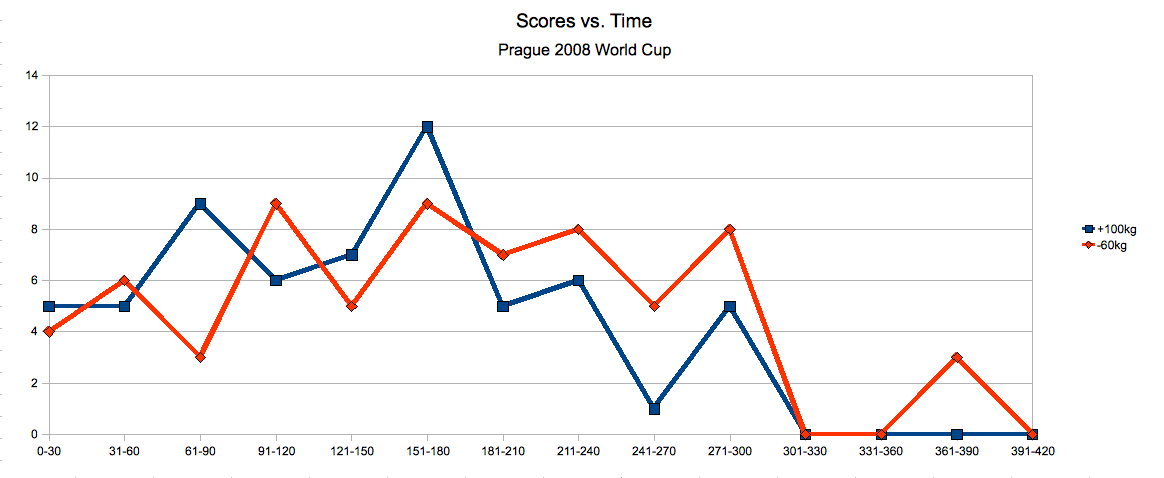

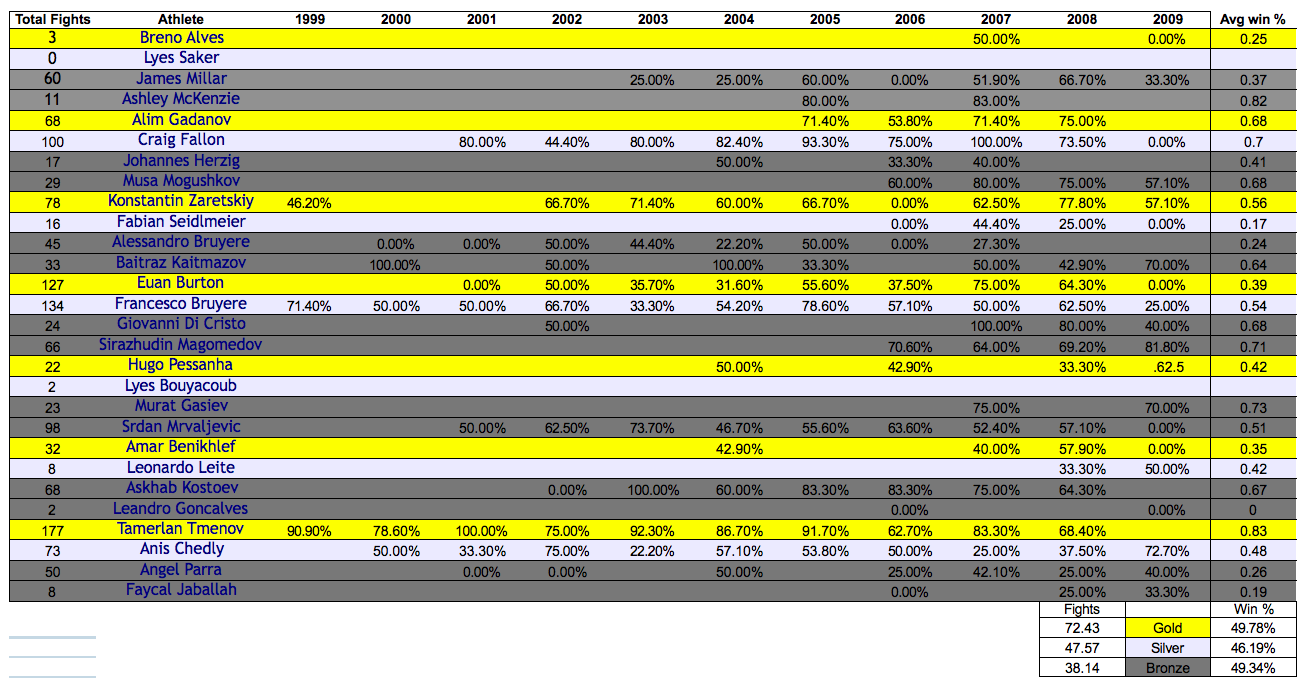

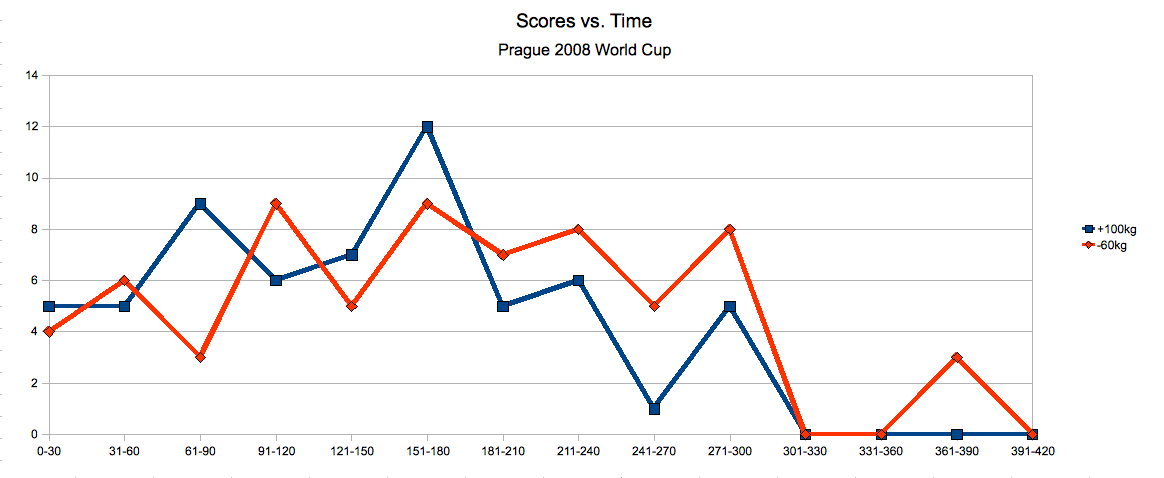

For example, we need to look at the weight category that your Judo athletes are competing in, below are chart is from the -60kg and +100kg categories, does it tell a different story?

The above chart shows some differences between weight categories that are interesting. The +100kg category shows a marked drop off in scoring after the peak at 151-180 seconds. The -60kg players appear to show a more consistent scoring pattern across the duration of the matches. This may be purely due to the physical characteristics of the players in these weights, we do not know.

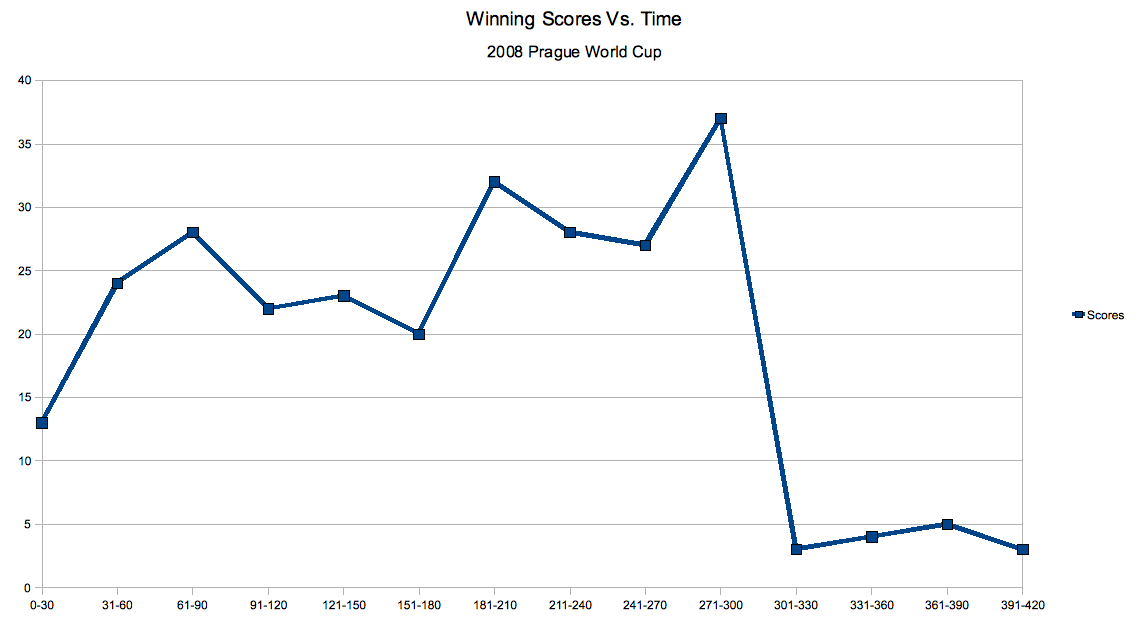

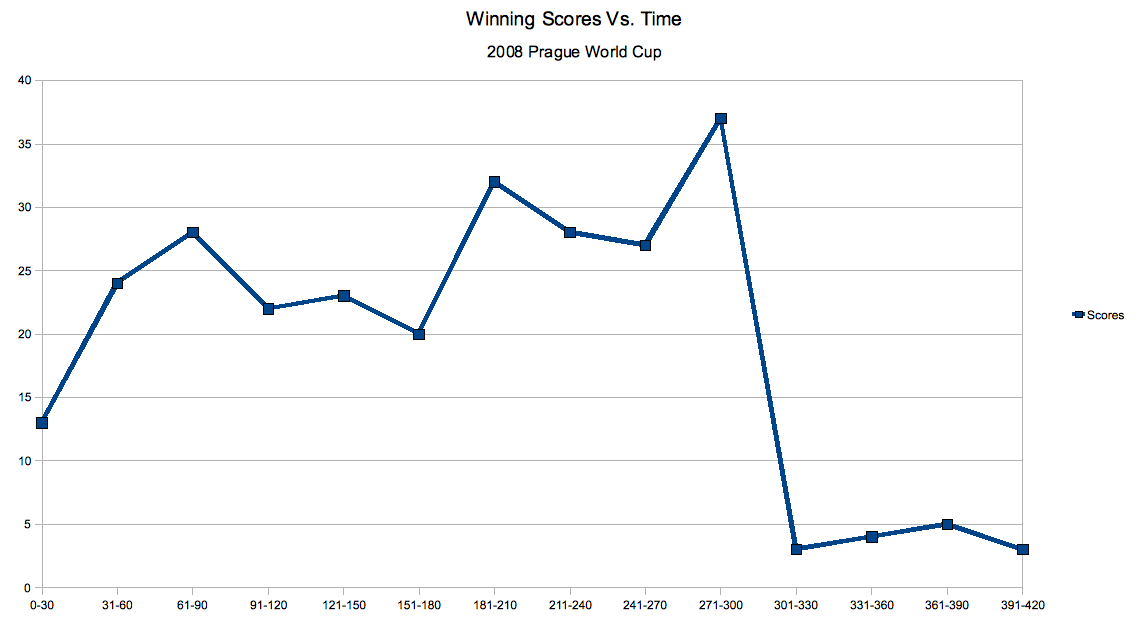

Both the charts above include all scores in the matches, which is interesting but argueably less interesting that when the decisive, winning score occurs in a match. Luckily, we have this information too.

The chart above suggests that there is a period of risk after around one minute, around three minutes and finally near the end of the match. The numbers of scores in these “hot spots” increases as the match goes on. The “dips” may indicate periods where players are resting? Perhaps we can train players to attack in the dips, where the majority of players are not scoring? This is one perspective of the data at least. Again this is data covering all attacks and all categories, lets look more closely at the data for individual categories.

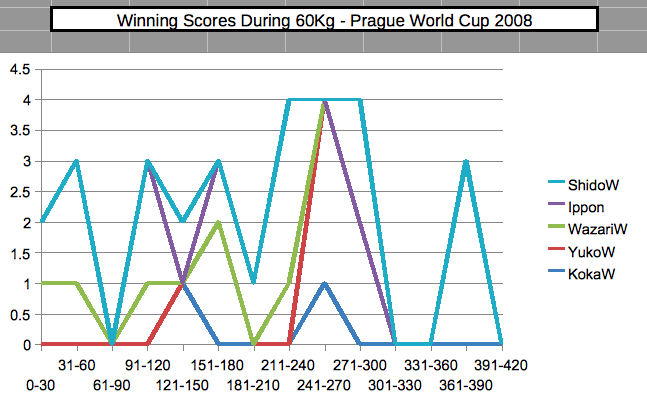

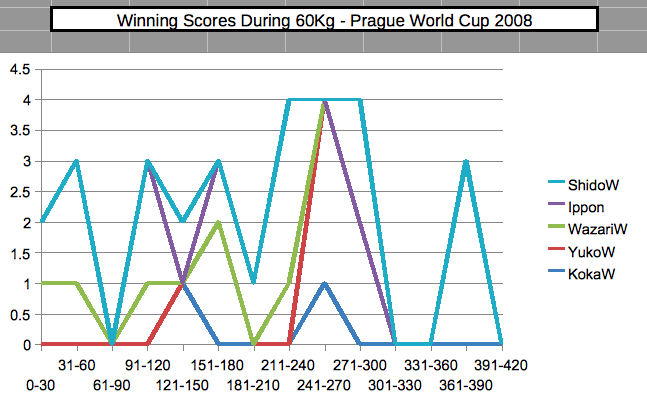

This chart shows when the scores that won the matches occured in the -60kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup. From this we can infer that the period from 211 seconds through 300 seconds is the “hotspot” at which point you are at the greatest risk of being scored against (or of course you have the greatest opportunity for scoring). Players can be trained (potentially) using methods that capitalise on this identified “hotspot”.

This chart shows when the scores that won the matches occured in the -60kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup. From this we can infer that the period from 211 seconds through 300 seconds is the “hotspot” at which point you are at the greatest risk of being scored against (or of course you have the greatest opportunity for scoring). Players can be trained (potentially) using methods that capitalise on this identified “hotspot”.

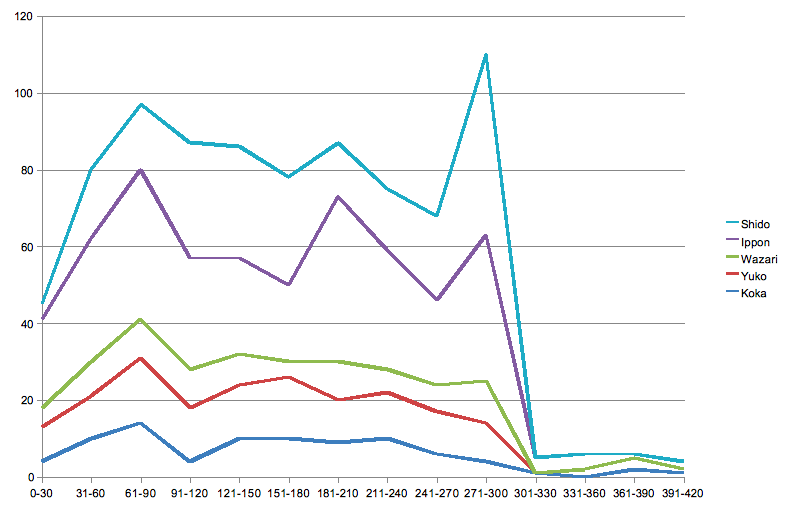

Here, for the first time we also see shat scores are occurring when. Shido is sadly the most common score. Let us now look at a entirely new category, the -81kg category.

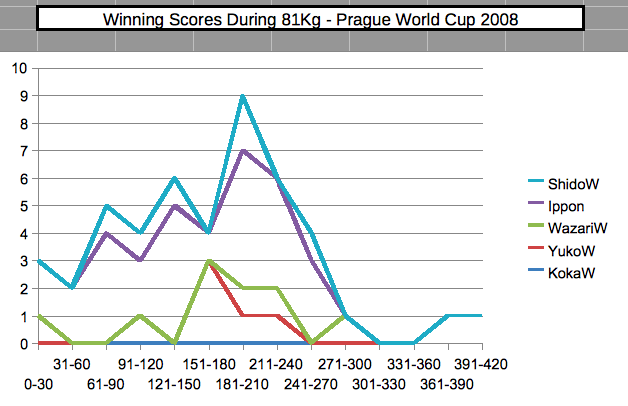

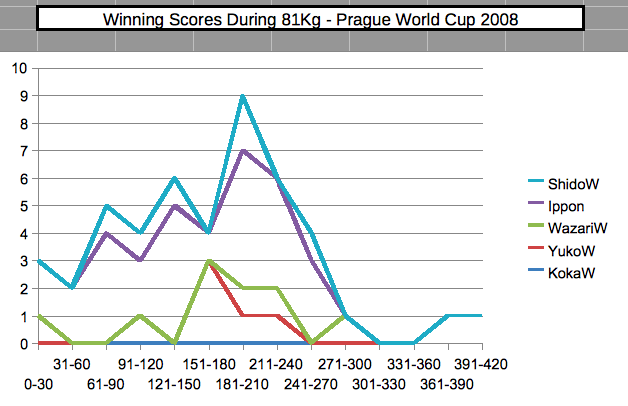

This chart of the -81kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup shows a very different shape to matches. Here there appears to be a steady increase in scoring up to the 181-210 mark, at which there is a sharp decline. There are a variety of ways this information might be used; perhaps if your athletes can be trained to withstand the onslaught leading up to the 211 seconds mark they might profit from planning their own barrage later in the match?

This chart of the -81kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup shows a very different shape to matches. Here there appears to be a steady increase in scoring up to the 181-210 mark, at which there is a sharp decline. There are a variety of ways this information might be used; perhaps if your athletes can be trained to withstand the onslaught leading up to the 211 seconds mark they might profit from planning their own barrage later in the match?

What is also interesting in this category is the large gap between Shido and Ippon scores and Wazari, Yuko and Koka scores. There is also what looks like a clear relationship between the Ippon and Shido scores, the peaks are consistently at the same places. What does this suggest? Why is there a difference between this category and the -60 fighters?

Perhaps at this point it is worth considering the overall scoring rate again, but look at the individual scores rather than an amalgamated chart:

This chart shows some interesting data that might be of interest. For example, the jump in Shido scores at 271-300 might show the penalties that accrue as a player ahead on points defends their lead at the end of a match. It is also clear that Shido is the top socre in this event, followed by Ippon, Wazari, Yuko and lastly Koka.

Perhaps it is data like this that served as proof to the IJF to scrap the Koka in international competition, seeing as it is clearly the least frequest score. Perhaps now that Yuko incorporates (some) Koka a future investigation might have Yuko more frequent than Wazari?

In terms of player preparation, can we apply what the data shows us? Should we be teaching/training Koka Judo? Is it an effective use of training time? Even at the “golden score” (301-420) stage of the fight Koka is infrequent. Should more time be dedicated in training to preventing or generating Shido?

The data from this study is fascinating, and it is interesting to consider the implications it might have in modern Judo preparation and competitive tactics and strategy. This sort of study and our own analysis of it in terms of our own specific situations may highlight potential changes in training or performance Judo that we can implement.

To close, I would like to thank Dave Elmore once more for sharing the data he collected with me and allowing me to share it online. Dave is doing great work which is not only statistical in nature. here in the UK he is perhaps better known for his work in the Advanced Aprenticeship In Sporting Excellence JUDO (and blog). If anyone is interested in enrolling for this course in September 2009 here is a document which gives more information and contact info: what-is-aase-word-doc.

Lance.

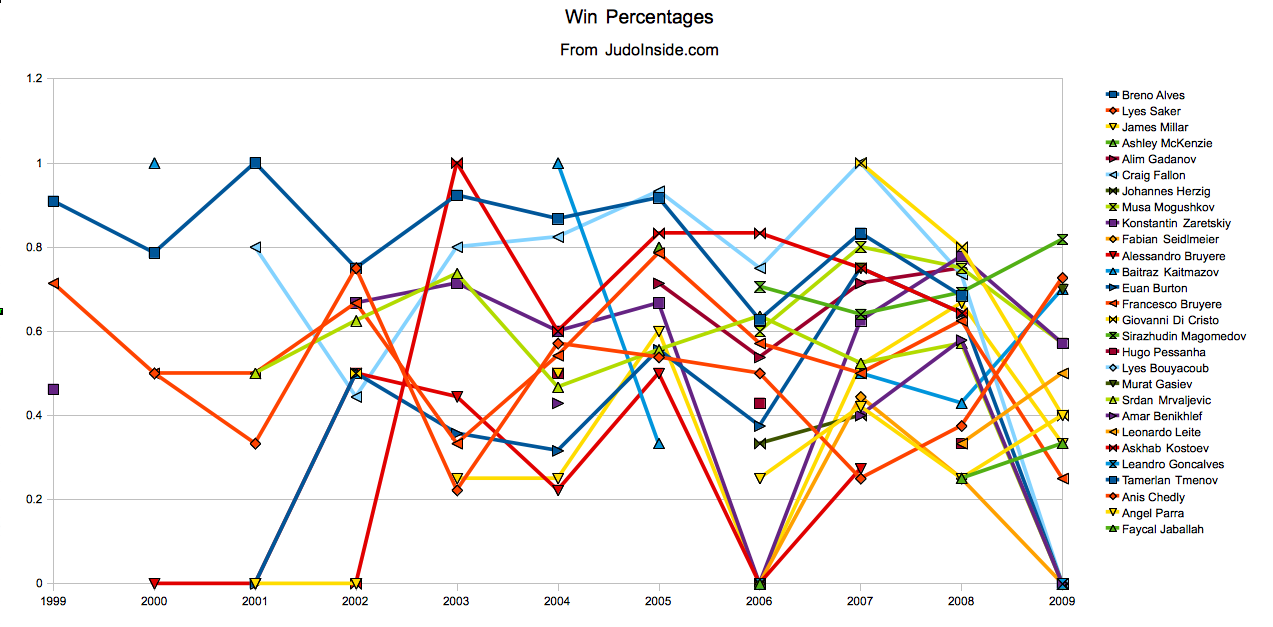

In this article we look at the ages of Judo athletes and of Freestyle Wrestlers at the Olympic level, this follows on from the article back in March (2009) on the “Ages of medalists at 2009 Judo World Cup events.” in which the age of Judo athletes competing at a high level was briefly examined. In this article we look at ages of athletes in more detail and compare Judo against our Olympic cousins Freestyle Wrestlers.

In this article we look at the ages of Judo athletes and of Freestyle Wrestlers at the Olympic level, this follows on from the article back in March (2009) on the “Ages of medalists at 2009 Judo World Cup events.” in which the age of Judo athletes competing at a high level was briefly examined. In this article we look at ages of athletes in more detail and compare Judo against our Olympic cousins Freestyle Wrestlers.

In this post I want to look briefly at the statistics from the Moscow Judo Grand Slam 2009. I am going to base it on the information gained from the great website

In this post I want to look briefly at the statistics from the Moscow Judo Grand Slam 2009. I am going to base it on the information gained from the great website

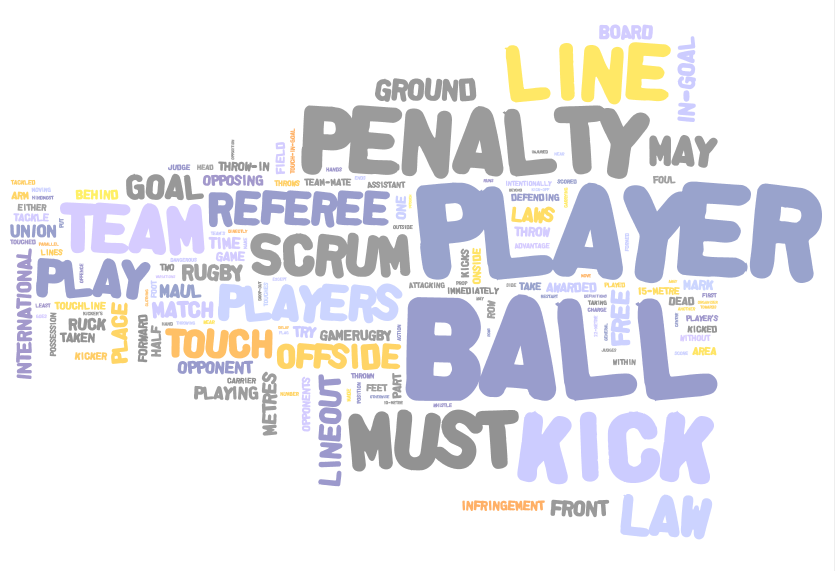

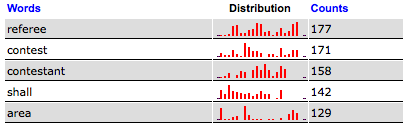

This table shows us again the importance of the word Referee and adds to our investigation by showing the distribution of the top 5 words throughout the rule book.

This table shows us again the importance of the word Referee and adds to our investigation by showing the distribution of the top 5 words throughout the rule book.

This chart shows when the scores that won the matches occured in the -60kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup. From this we can infer that the period from 211 seconds through 300 seconds is the “hotspot” at which point you are at the greatest risk of being scored against (or of course you have the greatest opportunity for scoring). Players can be trained (potentially) using methods that capitalise on this identified “hotspot”.

This chart shows when the scores that won the matches occured in the -60kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup. From this we can infer that the period from 211 seconds through 300 seconds is the “hotspot” at which point you are at the greatest risk of being scored against (or of course you have the greatest opportunity for scoring). Players can be trained (potentially) using methods that capitalise on this identified “hotspot”. This chart of the -81kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup shows a very different shape to matches. Here there appears to be a steady increase in scoring up to the 181-210 mark, at which there is a sharp decline. There are a variety of ways this information might be used; perhaps if your athletes can be trained to withstand the onslaught leading up to the 211 seconds mark they might profit from planning their own barrage later in the match?

This chart of the -81kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup shows a very different shape to matches. Here there appears to be a steady increase in scoring up to the 181-210 mark, at which there is a sharp decline. There are a variety of ways this information might be used; perhaps if your athletes can be trained to withstand the onslaught leading up to the 211 seconds mark they might profit from planning their own barrage later in the match?