With the Ukraine invasion by Russia, the sporting world has joined nations in placing sanctions on Russia. The IJF has banned Russian Athletes from competing.

In this article we briefly examine the impact this may have on Judo events in 2022.

Hypothesis

Russia is considered a string Judo nation, the men’s team at London2012 was dominant for example. The ban of Russian athletes may weaken Judo events.

Methodology

Using the Webservice::Judobase module and Perl programming language collect all the inscriptions from events across multiple years and sum the events and number of Russian athletes.

Results

Raw initial data:

{

'2015' => {

'Russians' => 815,

'total_events' => 59

},

'2016' => {

'Russians' => 734,

'total_events' => 58

},

'2017' => {

'Russians' => 718,

'total_events' => 58

},

'2018' => {

'Russians' => 824,

'total_events' => 62

},

'2019' => {

'Russians' => 763,

'total_events' => 60

},

'2020' => {

'Russians' => 165,

'total_events' => 18

},

'2021' => {

'Russians' => 492,

'total_events' => 38

}

};Discussion

The data shows a big drop in participation in 2020 and 2021. This could be in due to:

- Prior/Existing bans

The doping scandals had already impacted Russian participation and caused calculation of metrics more difficult as athletes have competed under different flags such as RJF (Russian Judo Federation). - Pandemic

2020 to now has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with event cancellations and travel limitations. Also the 2020 Olympic games were delayed till 2021. - Geographic diversity

A presumption can be made that Russian athletes are attending in larger number the events closer to them geographically. So an exploration of events to see what events Russian’s were attending and compare the impact would be of interest.

Extended data

By including athletes who participated as RUS, RJF (Russian Judo Federation) or ROC (Russian Olympic Committee) we can obtain a better count of Russian athletes.

{

'2015' => {

'Russians' => 815,

'total_events' => 59

},

'2016' => {

'Russians' => 734,

'total_events' => 58

},

'2017' => {

'Russians' => 718,

'total_events' => 58

},

'2018' => {

'Russians' => 824,

'total_events' => 62

},

'2019' => {

'Russians' => 763,

'total_events' => 60

},

'2020' => {

'Russians' => 165,

'total_events' => 18

},

'2021' => {

'Russians' => 523,

'total_events' => 38

}

};This boosts the numbers in 2020, where Russian athletes competed in Tokyo2020 under their Olympic Committee flag.

Another sample we can explore is the numbers from 2022 up till now:

{

'2022' => {

'total_events' => 55

}

};

This is for inscription for all of 2022, taken on 17 March 2022. So majority of inscriptions are till early April; however their are some inscriptions as far ahead as the December 2022.

Surprisingly the data did not show any Russian athletes have participated in events in the first quarter of 2022.

Summary

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia is a terrible thing and the impact of the International Judo Federation banning of the nation is a small triviality compared to the loss of life, harm and lives thrown into turmoil.

However, as trivial it is in comparison; it will have an impact on the sport of Judo.

Further research

It would be interesting to explore the medals won by the Russian athletes along with participation numbers to determine the change in depth of talent in the events.

If you are interested in exploring this, I would like to assist.

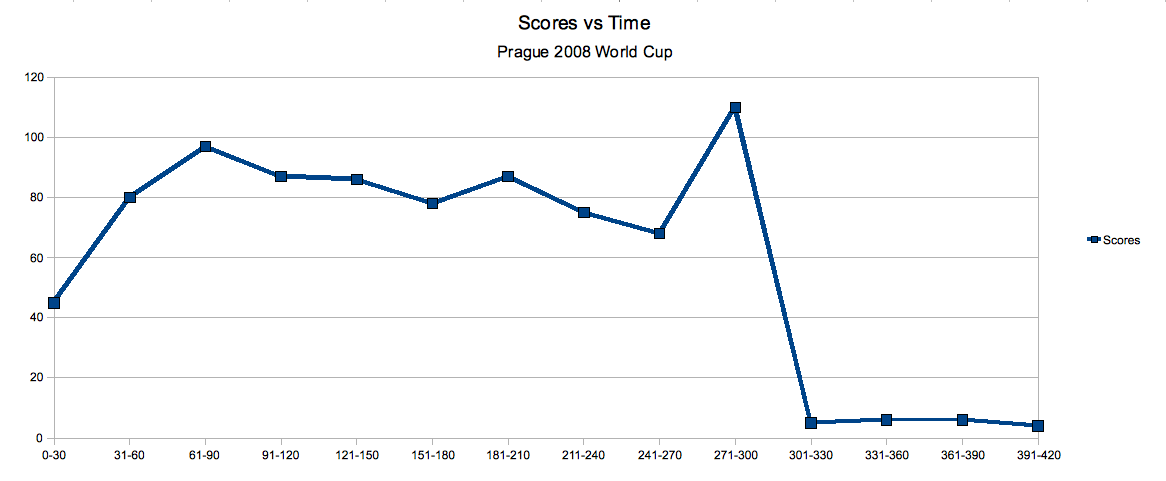

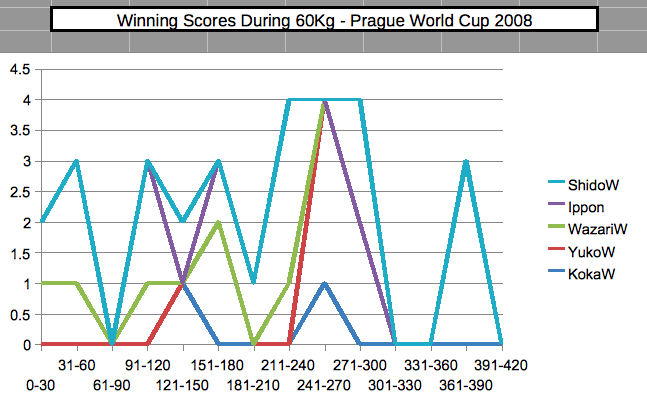

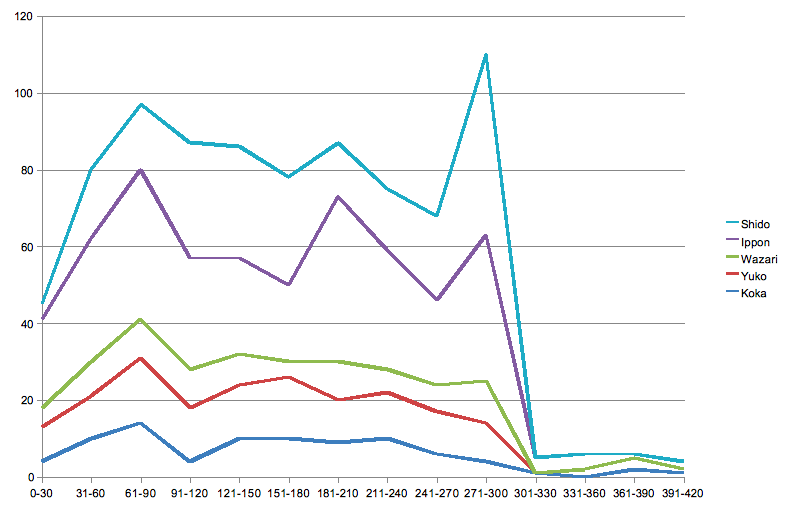

This chart shows when the scores that won the matches occured in the -60kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup. From this we can infer that the period from 211 seconds through 300 seconds is the “hotspot” at which point you are at the greatest risk of being scored against (or of course you have the greatest opportunity for scoring). Players can be trained (potentially) using methods that capitalise on this identified “hotspot”.

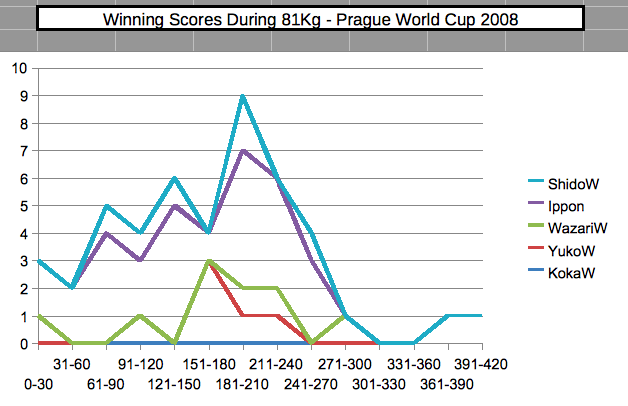

This chart shows when the scores that won the matches occured in the -60kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup. From this we can infer that the period from 211 seconds through 300 seconds is the “hotspot” at which point you are at the greatest risk of being scored against (or of course you have the greatest opportunity for scoring). Players can be trained (potentially) using methods that capitalise on this identified “hotspot”. This chart of the -81kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup shows a very different shape to matches. Here there appears to be a steady increase in scoring up to the 181-210 mark, at which there is a sharp decline. There are a variety of ways this information might be used; perhaps if your athletes can be trained to withstand the onslaught leading up to the 211 seconds mark they might profit from planning their own barrage later in the match?

This chart of the -81kg category of the 2008 Prague World Cup shows a very different shape to matches. Here there appears to be a steady increase in scoring up to the 181-210 mark, at which there is a sharp decline. There are a variety of ways this information might be used; perhaps if your athletes can be trained to withstand the onslaught leading up to the 211 seconds mark they might profit from planning their own barrage later in the match?

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1f75443a-fc30-4eac-b34c-a5a43faee74b)